I left my heart in Machu Picchu

Transformative travel, the value of local guides, and tourism as a double-edged sword

Within hours of arriving in Cusco, I threw up. My general malaise had turned to a pounding headache which had turned into me standing in the bathroom at our lunch spot staring at the toilet. Cusco, the ancient capital of the Incas, sits in the Andes at 11,000 ft above sea level. I was experiencing altitude sickness, which can be alleviated by drinking coco leaf tea like the locals do, staying hydrated, taking it slow, and by simply moving to a lower elevation as fast as possible. I had never been up this high above sea level, and my body was protesting. My parents and I spent the previous three days in Lima, established by Conquistadores as the present day capital of Peru, which sits just above sea level. Fortunately, our schedule allowed us multiple days to acclimate to the altitude before our true destination: Machu Picchu.

One of the seven wonders of the world, Machu Picchu sits 7,000 ft above sea level. A few years ago, a friend mentioned to me that the number of entries into Machu Picchu would be restricted soon, and I told my parents who had apparently been wanting to visit for 15 years. My reasons were not as serious; I like photography, hiking, and architecture. I studied Spanish in school for many years. More than anything, I supposed seeing Machu Picchu was just something I should do. Cross it off the bucket list. From May 12 to 23, 2025, my parents and I spent 11 days traveling across Peru. My visit ended up more engaging and thought provoking than I ever thought it would be.

“Peru’s fascinating history is in evidence everywhere: in mortarless Inca stones that serve as foundations for colonial churches, in open graves with bits and pieces of ancient textiles, and in traditional dress, foods, and festivals, as well as strongly held Andean customs and beliefs” (22). “In Peru the divide between rich and poor, coastal elites and indigenous highlanders, and modern and traditional, continues to loom large. All those unfortunate years of corrupt politicians, lawlessness, and economic disarray may have clouded but never eclipsed the beauty and complexity of this fascinating Andean nation” (24). “Visitors to Peru will discover a country and a people rooted in a glorious past but looking forward to a future of new possibilities” (22).

—Frommer’s EasyGuide to Lima, Cusco, and Machu Picchu

In Cusco, even the slight uphill walk to the hotel had me breathing heavily. This never happened to me in hilly Seattle, but in higher altitudes, the air is thinner and contains less oxygen. My lungs worked overtime trying to suck enough in. I did drink coco leaf tea like the locals do, but still threw up and napped for hours afterwards. Compared to the incredibly crowded, sprawling metropolitan city of Lima with 10 million people or ⅓ of all Peruvians, Cusco, with less than 1 million people, is much older with its narrow cobblestone streets. Its plazas still bustle with people, mostly of indigenous descent. The rainbow, Chuychu, appears as the seven stripes in modern day Cusco’s flag.

“Cusco” in the native language Quechua means “navel” because it sat at the center of the Inca empire as its capital.

As I would come to see with my own eyes, the Incas were incredible architects and farmers. Even before their short rule of around 100 years, the Andean societies before them (like the Wari, the Moche) revolved around agriculture. They studied the stars to predict good and bad harvests. They named the earth, Pachamama, and the sun, Inti, as the first couple. The earth needs the sun to grow life and have light. The sun needs the earth to have something to nurture. Their sun temples and human (and llama) sacrifices and calendar and astrology were all in the name of good harvests. During the summer equinox, they celebrated Inti Raymi to bring the sun close to the earth again.

I would come to learn that Peru still relies on farming. But another industry has climbed the ranks: tourism. At least one million tourists visit Machu Picchu each year. It quickly became clear to me just how deeply rooted tourism is in today’s Peru.

My parents and I toured Cusco and neighboring areas with a guide, Pablo from Cusco Local Friend. I had never traveled with a guide in recent memory, but my dad thought it best to have one due to Machu Picchu’s complex ticketing system and the foreboding KM 104 hike along the Inca Trail.

Throughout the week, we visited historic sites like Sacsayhuaman, Chinchero, Maras, Moray, Qorikancha, Ollantaytambo, and of course, Machu Picchu. I saw that the Incas were brilliant architects who built upon the natural shape of the mountains. For sacred sites like temples, they pushed large, polished, smooth stones seamlessly together with nothing but concave and convex notches carved between them, like Legos. Pre-Columbian Andean people were incredibly resourceful and masterful, able to build lasting stone structures in a volatile seismic zone—Peru is located in the ring of fire.

At Maras, we saw the Andean’s original way of farming salt from a stream from within the mountain whose salinity was higher than seawater. Pablo told us that these days, local indigenous families made an arrangement to continue using Maras to farm salt the ancient way without government intervention. We watched them perform the backbreaking work of hammering clay into the bottoms of pools that would fill with salt water. They have begun exporting their product, Marasal, which I was lucky to sample and bring home. “I think it’s going to be big,” Pablo said. Having just cooked Andean quinoa soup with it, I have to agree.

At a small outpost called Manos de la Comunidad, a staff member brought us to pens of alpacas, llamas, guanacos, and vicuñas, known as the South American camelids. As we fed them oat grass, she explained that the Andean people domesticated the llama first, then the alpaca. They considered llamas sacred and used them primarily for transport instead of eating; their meat is too tough anyways. They used alpacas for everything including their meat and soft wool. Considered some of the finest in the world, baby alpaca and vicuña wool are some of Peru’s most well-known exports.

There, we also saw condors, which to the Andean people represent the sky. The puma represents the earth, and the snake the underworld.

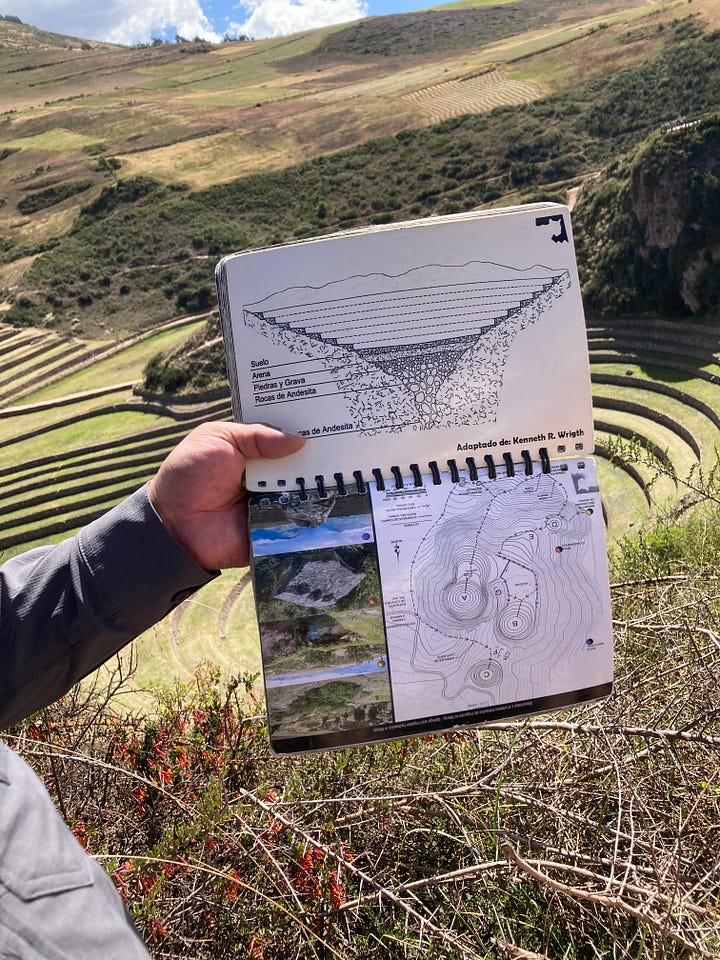

The Andean people were, and still are, incredible farmers. At Moray, we saw where the Incas tested and hybridized crops for optimized harvests. Located centrally between the mountains and the cloud forest, the four circular farming terraces contain distinct climates of varying altitudes and temperature. The Incas used these to acclimate crops from distinct climates (the mountains, the cloud forest, the coast) to grow in different climates so their harvests could be accessible across the empire. Incas planted crops naturally found in lower elevations first in the lowest elevation terraces, then moved them to higher and higher ones. If the crop succeeded to acclimate while retaining its quality, it moved to the higher rings until graduating to grow across the empire. It was the reverse for crops naturally occurring at higher altitudes; they started high and ended low. Moray, known as the “greenhouse” of the Incas, helped them cultivate crops including quinoa and thousands of species of corn and potatoes, which are still farmed today and consumed worldwide. We know this because of crop remnants and soil makeup archeologists uncovered. Yet, when I was trying to tell friends how brilliant Incan agricultural innovations were, I could find little information about Moray’s true purpose online. One article even mentioned a conspiracy theory about aliens.

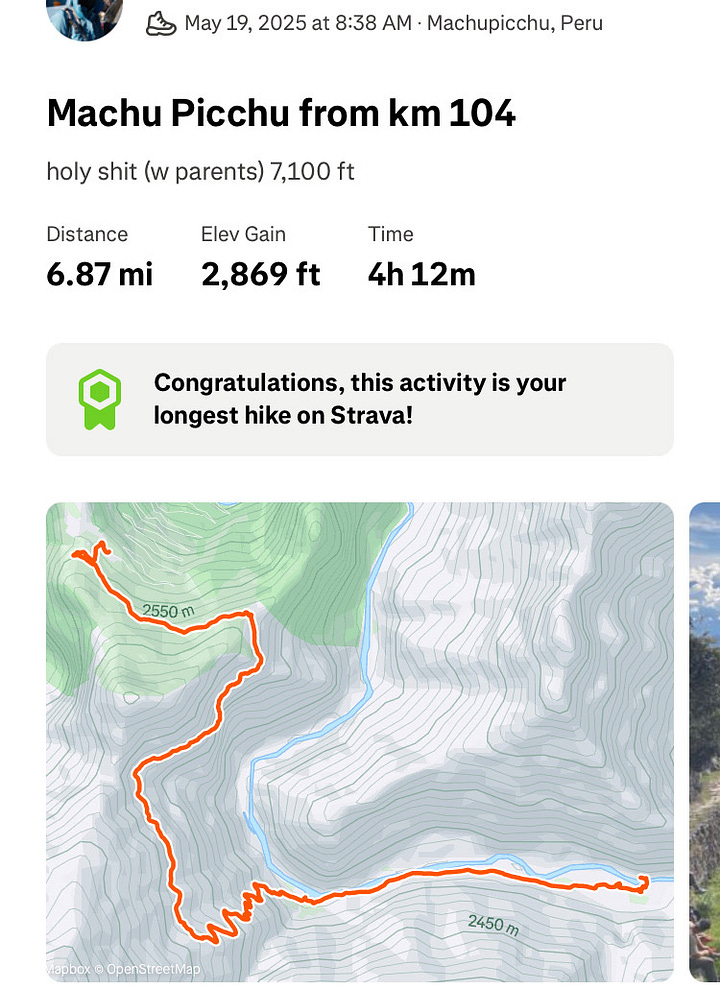

Living in Seattle without a car for the better part of a year meant that feeling of being out of breath from stairs was uncommon for me. But as we traveled to more and more sites, I adjusted to the high altitude. By the time we hopped off the train to begin hiking KM 104 of the fabled Inca Trail, the original route the Incas built from Ollantaytambo to Machu Picchu, I was ready.

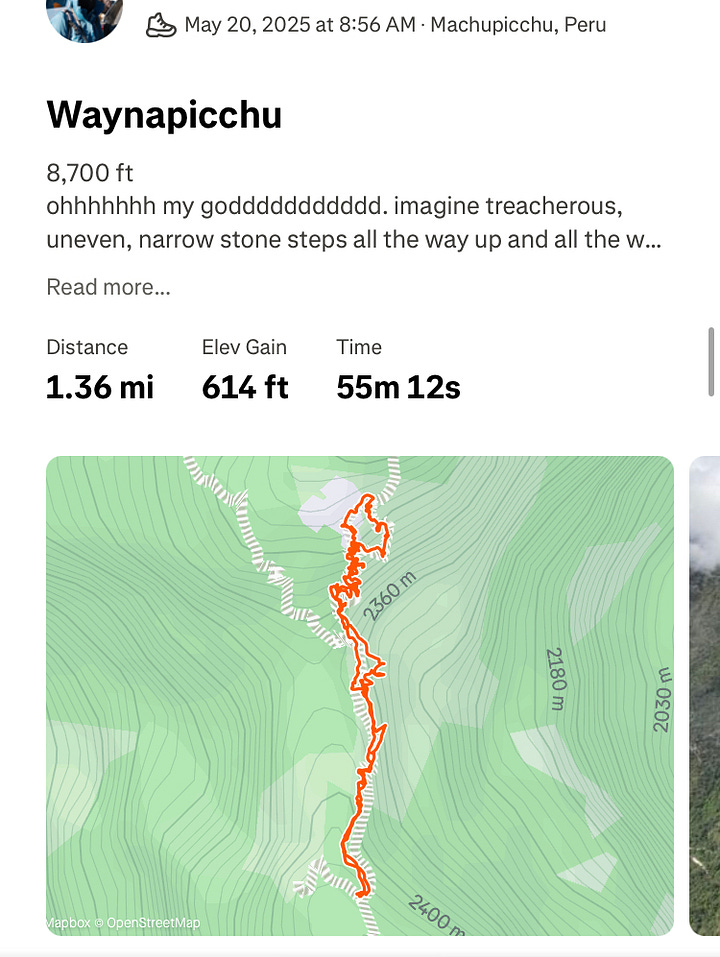

Pablo has been a guide for 20 years. Hiking with him, I never saw him break a sweat. He didn’t use hiking poles and effortlessly climbed up and down each mountain. I asked him how many times he’d climbed the steep and arduous Waynapicchu, the taller mountain behind Machu Picchu in classic photos. He said two to three times a week. He’d done this thousands of times.

KM 104 and Machu Picchu are littered with big and small tour groups speaking a variety of languages, mostly English (likely from USA and Canada) and Spanish (likely from other South American countries and occasionally from Spain).

I asked Pablo what percentage of working Peruvians are in tourism.

“The majority,” he said. “Guides, hotels, restaurants, everything related.”

Tourism in Machu Picchu and surrounding areas looks like a well-oiled machine. Bus drivers expertly made three-point turns in Aguas Calientes’ narrow cobblestone streets, hanging the bus’ entire rear end over the river, and fluidly avoided other bus drivers by backing up or squeezing by. Porters carrying huge backpacks swiftly ran up and down the mountain ferrying supplies for campers and hikers. During our day hike from KM 104, we must have seen more than thirty. It seemed like an entire ecosystem.

On the bus ride down from Machu Picchu the first day, I happened to sit next to an interpreter. She spoke four different languages (English, Spanish, Chinese, and Korean) and told me that Peru once had three different presidents in one year because they are so easy to overthrow. I wistfully imagined this occurring in the USA for a second before asking if she thought that was good or bad.

“Bad,” she said. “Because it creates instability.”

Another time I noticed political signage up and down the streets of Urubamba and asked Pablo about voting in Peru. The next presidential election occurs in 2026.

Pablo told me that people in Lima vote very differently from people in Cusco. I could see that more Cusqueños seemed to live in the older Andean way, compared to people in Lima. My dad pointed out that Cusco’s population is mostly of indigenous descent rather than Spanish descent, unlike Lima’s. “These two groups will always have conflict,” he said.

Pablo’s vast knowledge of Peru was evident by the way he answered every single one of my family’s questions about history, culture, flora and fauna, food, politics, without having to consult his worn coil-bound book all guides carry. Descended from indigenous Andean people, he and his seven siblings were born in Urubamba, a town in the Sacred Valley, to farmers. Now, he guides tourists several times a week in Machu Picchu and its surrounding areas. On all of our hikes, he remained calm and collected. He never seemed to exert himself. He didn’t use hiking poles. He always noticed flora and fauna which he pointed out to us. He knew when we needed to take breaks and where the best photo opportunities were. He also seemed to know many non-tourists we encountered. It seemed everyone knew everyone in this well-oiled machine that is Peruvian tourism.

But during the pandémia, Pablo explained, tourism came to a stop. Peruvians returned to farming. “We always have, and we always will,” he said.

After graduating in 2021 during the pandemic, I moved back to my hometown of Dallas, Texas to work remotely as a UX Designer. A little over a year ago, I decided I wanted a change of pace and moved to Seattle, Washington to try it out for the summer. The freedom of being able to get where I wanted without a car was exhilarating. Instead of having to drive to the gym, the park, the grocery store, a friend’s place, I could just walk or take public transit. I was still experiencing all the difficulties involved with adjusting to a new city, but in the middle of June I met someone who made me feel I belonged in Seattle. The first time I visited his apartment, I noticed a flag hanging from the wall.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“Dude,” he replied. “Cascadia.”

I learned that he was born in LA but went to college in Oregon where he fell in love with Cascadia. After college, he worked in LA for a year and hated it before begging to be relocated to the Seattle office instead. The idea that he loved this place enough to chase after it and fight to stay inspired me. I hadn’t felt that way about my hometown of Dallas or my college city of St. Louis. I thought it might be nice to feel that way. To feel so rooted to a place that you call it home.

According to Pablo, life expectancy in Lima is around 70 years. In Cusco, it’s 80. In the Andes mountains, it’s 90, or even 95. Andean people eat the crops and animals they themselves care for. And they traverse mountains by foot, even at old age. Most are farmers. It takes some children hours to walk to school. This kind of necessarily active lifestyle, one I tasted in Seattle, makes people stay healthy and mobile longer. Compared to how I was living in Dallas, living in Seattle for less than a year made my body feel stronger than ever and ultimately prepared me for hiking in the Andes. My friend and I call this the “gym of life.”

I asked Pablo if he’d ever take up the family farm. “Probably,” he said. He wants to retire to Urubamba where it’s quieter. He and his siblings are trying to get their dad to retire from farming at his old age, but he refuses. Apart from his biologist brother who moved to Germany, his siblings still live in Peru as well.

From quinoa vendors to textile weavers to drivers to guides to hotel receptionists, everyone seemed to love this place, a lot. Good at math, Pablo enrolled in a civil engineering major at university before his older biologist brother inspired him to become a guide instead. He switched his major to tourism freshman year. I’d never heard of such a thing in the US. We have tourists, but our tourism industry is nothing compared to Peru’s. It’s not a well-oiled machine. It doesn’t have to be, because we’re not dependent on it.

Conversely, tourism is one of, if not the, largest industries in Peru.

The country has undergone so much political instability that I was surprised by how friendly Cusqueños were to me. My parents described them as “honest,” especially compared to locals in other places like Shanghai (my mom’s hometown). At the Mercado San Pedro, while searching for choclo (a corn cultivated by the Andeans with huge white kernels) to make popcorn with, I asked various shopkeepers in Spanish whether their products could be made into popcorn. One said, “Yes, but you need a special machine.” Another said, “No, these are for toasting.” Another said “No, these don’t open up like popcorn.” My parents said, “In Shanghai, if you asked if you could make popcorn with these kernels, they would’ve just said, ‘Yeah yeah yeah, you can do anything with these,’ and encouraged you to buy them.”

All licensed guides carry a government-issued badge and a coil-bound book filled with information about Peru. At each site, Pablo showed us diagrams and pictures illustrating historical context. Moray, Maras, and Machu Picchu are some of the only sites we visited without Spanish structures. In Ollantaytambo, Pablo explained, the Spaniards kept the original city layout and built stories on top of it, so all second floors are Spanish, and all first floors are Incan. We saw this again and again in places like Qorikancha, a temple turned Spanish cathedral, and Chinchero.

Pablo showed us the outside of Chinchero’s cathedral—its roof was under renovation so we couldn’t go in—and explained that it’s one of two Peruvian sites with fresco paintings, a European method. The Spaniards got locals to paint Catholic frescoes for this cathedral. During the conquest, Pablo said, Andeans resisted in small ways. Instead of painting the traditional European Catholic saints, locals painted their own interpretations as a way of preserving Andean culture. Pablo demonstrated: because Andean people were always climbing up and down mountains, their knees couldn’t stand completely straight. None of the locals’ depictions could, either. They were shorter—many mountainous people including Himalayans are short due to the extreme altitude. They also had dark skin, Pablo said, pointing at his own hand.

In other Catholic-Peruvian paintings we saw in Lima’s San Francisco Convent, local painters depicted Mary with a triangular silhouette reminiscent of the mountain, representing Pachamama, mother earth. “Pacha” in Quechua refers to the space-time continuum. Depictions of the last supper showed a round table instead of a long rectangular one, and cuy or fish sat on the center plate.

I asked Pablo if there’s still resistance today. He told me that 70-80% of Peruvians are Catholic, but among them, only about 10% are solely Catholic. The rest practice the Andean way of life and Catholicism together; they celebrate Andean festivals like Inti Raymi (the sun festival) and Catholic holidays. The “pure” Catholics are of Spanish descent. In Cusco, it’s clear that the Andean way of life still persists.

A common motif in Cusco is the bull. Brought over by the Spanish for farming, the bull to the Andes people represents the relationship they have to the earth, to Pachamama. Two ceramic bull sculptures (called torito de Pucará) displayed in a household signifies protection. Households displaying a cross in between the bulls are Catholic; others are not.

In Chinchero, Pablo described how the last Inca king, while fleeing from Conquistadores, burned and destroyed each Inca town he passed through so his pursuers would have a harder time to find resources and a place to stay the night.

“Did it work?” I asked.

Pablo chuckled sadly and shook his head. “Ay, no.”

But it did slow the Spaniards down. They’d have to turn back to their last stronghold and begin the journey again with more supplies. I asked out of curiosity: what if we had more Incan artifacts and towns today? But in a way, it’s a moot point. The Inca kings followed strategies they thought were best. The Spaniards were hunting them down, not to kill them, but to obtain what was rumored to be the largest gold and silver artifacts the Incas ever made. I also learned that Conquistadores destroyed a lot of Incan towns they conquered as well. Ollantaytambo and Chinchero, which retained their original layout and first stories, were outliers. If the fleeing Inca king hadn’t ordered the destruction of the towns he passed through, the Spaniards might have.

Machu Picchu is one of the only Inca cities still intact. And that’s because the Spaniards never found it. It was covered by thick forest vegetation which hid it from view. Until Hiram Bingham in 1911 discovered it while searching for the “lost city of the Incas,” the final refuge of the fleeing Inca king (Vilcabamba), it wasn’t known by the outside world. Machu Picchu, abandoned under the fleeing king’s orders, was a place where the king placed the brightest minds of the empire: the elders who knew Incan history. The Incas had no written language and relied on oral history. Tested in school, the brightest of the younger generation were selected to move to Machu Picchu to study under the elders there.

The dearth between Pablo's expansive knowledge and what I can easily find on the internet is wide. Before my trip, Machu Picchu was shrouded in mystery. Sources I normally trust like Wikipedia claim that the purpose of Machu Picchu isn’t yet known. But it is. It’s known by Peruvians. To access this knowledge, one can dig deeper or visit Peru with a guide. But therein lies the paradox of tourism in Peru.

Tourism brings money to Peru, but it also prices out locals. Millions visit Machu Picchu each year, and their foot traffic degrades archeological landmarks, erodes the soil, and pollutes the earth. Without proper care, tourism has the potential to destroy Machu Picchu.

Threatened by larger parties like UNESCO, the Peruvian government has taken measures in recent years to decrease the number of entries per day for the sake of reducing foot traffic.

The Temple of the Condor in Machu Picchu depicts a condor. Large rocks form its left and right wings, and smaller rocks on the ground form its signature throat cuff, head, and beak. This is where the dead connect to the heavens. The condor brought them to the sky, while the snake brought their bodies and earthly possessions to the underworld to rest. The three sacred animals—the condor, the puma, and the snake—are recurring motifs in Peru. Cusco is said to be built in the shape of the puma, with the temple Sacsayhuaman as its head. Machu Picchu is said to be built in the shape of the condor.

I noticed Pablo wore a pendant around his neck, a symmetrical arrangement of thirteen squares in the seven colors of the rainbow. I kept seeing the same symbol all over Cusco—on walls, on furniture, on textiles—and thought it was the Inca calendar. I had difficulty finding information about the Inca calendar online, so I asked Pablo about its significance.

“Farming,” he said.

I realized I was asking about the wrong thing. “No,” I said. “What is that?” I pointed to the symbol painted on the wall across the street.

“Oh,” he said. “That is the Chakana. Some people call it the Andean cross, but it is not a cross. The cross is European. The Spaniards brought Catholicism and the cross here. No, the Chakana represents the bridge between worlds. At the top, the sky, represented by the condor. The middle, the earth, represented by the puma, and the bottom, the underworld, represented by the snake. And Cusco in the center.”

Wikipedia, a source I normally find trustworthy, has a page called “Chakana” that mostly refers to the symbol as the Andean Cross and claims its meaning is obscure. But it’s not. Not to Peruvians.

Can this information only be found from licensed guides? In the coil-bound books they carry? In the university classes they studied? Like the elders of Machu Picchu, will this information be lost with them?

The night after we hiked KM 104, we had dinner with Pablo as mandated by his agency Cusco Local Friend. Looking at the menu, he asked us what our favorite food in Peru had been so far.

“I tried cuy,” I said, referring to guinea pig.

“Cuy is traditionally eaten on special occasions like weddings or other large celebrations,” he said.

“I liked quinotto, quinoa risotto,” I said.

“Yes,” Pablo said. “The good quinoa is exported outside of Peru, so Peruvians no longer have access to good quinoa. This is generally what happens. The more something is shared with the world, the less of it Peruvians have.”

It’s delicate. Peru relies so heavily on tourism so tourists are treated well. Prices can’t be unaffordable. At Mercado San Pedro, a ½ kilo bag of quinoa costs 7 soles or 1–2 USD. Alpaca keychains cost 1 sol or ⅓–¼ USD compared to 20 soles or 5–6 USD at the airport’s duty free shop, and 9 USD on Etsy. The most expensive goods I encountered in Peru were those made of baby alpaca or vicuña wool, the softest of the South American camelids. Locals can’t rob tourists. Shopkeepers have to be honest. How much of it is about not biting the hand that feeds you?

Due to high turnover of corrupted presidents and political unrest caused by the Shining Path group in the 70s, Peru is wracked with instability. But Cusqueños seem to be trying to make the most of it. The love and pride Cusqueños feel for their heritage is infectious. Over and over again, I encountered bright, enthusiastic locals happy to share their knowledge with me. Even in the face of political turmoil and colonialism. Like Pablo wearing the Chakana around his neck, Cusqueños are working hard every day to uphold their Andean heritage.

Almost one year ago, I met someone who deeply loved Seattle and made me love it in return.

Being able to see a place through a local’s eyes is something I didn't expect to become the part of my trip I treasured most. Upon landing in Lima, I thought to myself that I couldn't imagine living there. But by the time it came for me to leave Cusco, I was sad to. Though I struggled with altitude sickness the first days, Cusqueños like Pablo taught me so much about their country that I had no choice but to love it too.

At his Seattle talk this February, Rick Steves said that travel should be transformative. I consider my trip to Peru some of the best travel I’ve ever done.

In Chinchero, a small town in the Sacred Valley, we stood on a green field overlooking the city and lush mountain pastures. Pablo said, “Soon this won’t be quiet anymore.”

When I asked why, he said an international airport was being built to replace the domestic airport in Cusco. Tourists normally fly into Lima’s international airport first, then Cusco. But in a few years, they’ll be able to directly fly to the Sacred Valley, currently only accessible via car and bus.

“Planes will fly over the Sacred Valley,” Pablo explained. “Chinchero will be expanded to a tourist town. It will no longer be this peaceful here.”

Thinking about the noise and air pollution in the valley where the Inca kings once lived, I asked, “Aren’t there any protections against that?”

He said that maybe there were, but after many years the idea of a lucrative international airport finally won.

What the upcoming international airport in Chinchero will lead to, I cannot say. Money, yes. Fame, yes. Recognition, yes. What it will also bring is air and noise pollution to the solitude of the Sacred Valley.

But seeing Cusqueños upholding ancient pre-Columbian ways of life reminds me how resilient they are against hardship, how true they stay to their beliefs.

I left Peru with a deeper understanding than I thought I ever would. For somewhere so complex, layered, and “shrouded in mystery” as Peru, having a guide was invaluable. Pablo taught me so much about his country that I was able to see glimpses of it from his perspective. Saying goodbye was bittersweet.

After all the hardship they’ve endured, I wish only the best for Cusqueños.

Hasta la próxima.

Note: This is not meant to be a research paper. It's more of a reflection on my own travels to Peru. I’m not trying to say that there’s no information about Peru outside of Peru, because I haven’t looked that closely. All I’m trying to say is that the easily accessible information online seems lacking. Your mileage may vary.

All views expressed are my own.

Sources: What I remember my guide Pablo saying, Frommer’s EasyGuide to Lima, Cusco, and Machu Picchu, Wikipedia

Image sources: Myself, my dad, Pablo

Peru recommendations: Museo Larco (Lima), La Mar (Lima), Chullpi (Ollantaytambo), Full House (Aguas Calientes), Yaku (Cusco), Pachapapa (Cusco), Waynapicchu (Machu Picchu), Cusco Local Friend agency

😩 not Strava making the article! Thanks for sharing your wonderful photos and words!!